‘The General of Wu’ Pt. 1

‘What of their number, General Tzu.’

‘No less than one-hundred-fifty thousand. No more than two-hundred thousand.’

‘And so what do your chapters have to say of Wu victory with an army of only thirty-three thousand strong.’

My sovereign, King Helü. I know my own temperament as General with no less constant than the five elements of Tao and the army which I command is as if of my own seed. Yet whilst in readiness for death there is nothing that a soldier cannot achieve, if I believed us in a condition to attack, but were uninformed of the enemies openness to be attacked, you would hear only half the story of victory. Should we become aware that the enemy is open to attack, yet remain ignorant to tells that our own men are in no condition to do so, still we would speak only a half-plot to victory. And should we find fortune that both the enemy are open, and we are ready to, attack, yet still we remain oblivious to an unfavourable nature of grounds making fighting impracticable, still we would hail the victory of a man half-blind.

My sovereign, King Helü. I know my own temperament as General with no less constant than the five elements of Tao and the army which I command is as if of my own seed. Yet whilst in readiness for death there is nothing that a soldier cannot achieve, if I believed us in a condition to attack, but were uninformed of the enemies openness to be attacked, you would hear only half the story of victory. Should we become aware that the enemy is open to attack, yet remain ignorant to tells that our own men are in no condition to do so, still we would speak only a half-plot to victory. And should we find fortune that both the enemy are open, and we are ready to, attack, yet still we remain oblivious to an unfavourable nature of grounds making fighting impracticable, still we would hail the victory of a man half-blind.

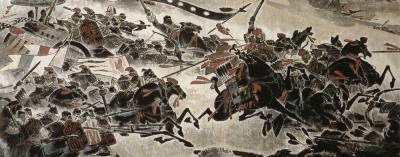

The King found an eerie comfort in this controlled estrangement not only from his new General but also the thirty-three-thousand men who that morning, on General Tzu’s command, had fed their horses with grain, killed the cattle for food and left their cooking pots discarded at the side of their camp-fires. It was a ritual for knowledge that they would not return to their tents, the setting clay of determination and readiness to fight until death.

Warfare had changed. No longer was it a knightly contest tied by strict code – a chivalrous sport for the nobles – and it was clear that his new General refused to adhere to archaic ‘rules of war’ which he claimed played with the lives of men and promoted the enduring suffering of the people. The King had never seen more than one expression set on the face of this man who only Spring past he had personally proclaimed ‘jewel of his kingdom’: his permanently tight brow was etched with deep fissures from mountainous furrows on a forehead set deep into a flat face of hardened slate. He sat upright, rigid in the same worn saddle he had ridden through winter winds and arrived the State of Wu from his home town Ch’i after the rebellion which had brought in its heart only ruin and death. His eyes were, glass, sharp, and he did not blink despite the burning freshness of Spring morning’s breeze. His gaze was fixed on both armies as one would the manifestation of a piece of precise art created entirely of the mind.

And Sun Tzu said:

‘My Sovereign. Though according to my estimate the soldiers of Chu exceed our own in number, that shall advantage them nothing in the matter of victory. I say then that victory can be achieved.’

柏舉之戰

End Pt. 1 ~ The Battle of Boju